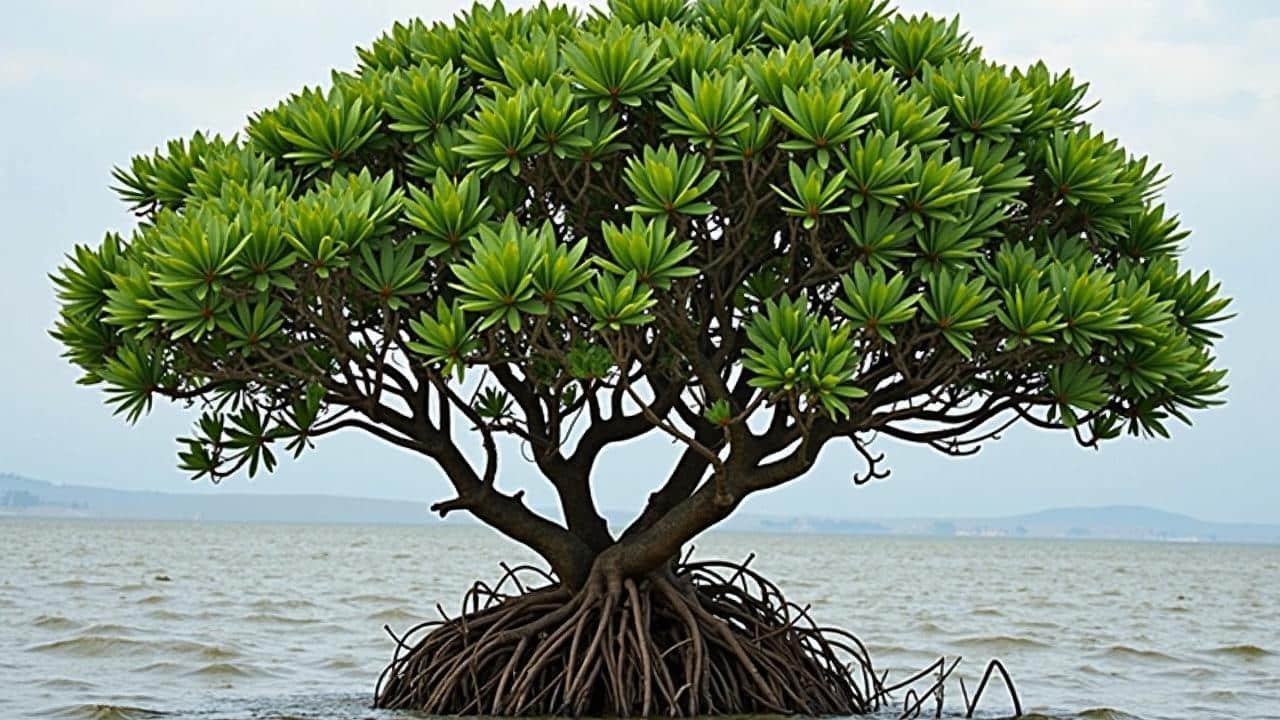

Skinny mangrove roots poke out of the mud, holding tiny crabs and glistening drops of seawater. A line of women in rolled-up trousers walk slowly, each carrying a plastic tub filled with baby mangrove trees. They press the seedlings into the wet earth, one by one, under a heat that feels almost solid.

Just a few years ago, this shoreline was a scarred strip of sand, bitten away by waves. Now, more than half a million young mangroves like these have been replanted around the world. They are changing things quietly: pulling carbon from the air, softening storms, inviting fish back home.

The work looks tiny at the scale of the planet. One seedling, one hole, one handful of mud.

Latest Posts

- With Just 1 Bottle of Water How I Was Shocked by What Happened When Growing Vegetables

- Maximize Your Home Garden with the Hanging Pea Sprout Growing Model – Space-Saving, High-Yield, and Easy-to-Manage Vertical Gardening Solution

- Just Water – The Secret to Growing Plump, White Peanut Sprouts Right at Home: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners

- Growing Zucchini at Home in a Container: How to Cultivate Large, Long Fruits with a 1-to-72 Day Step-by-Step Diary for Maximum Yield

- Grow Long Beans on the Terrace in Used Recycling Baskets: The Ultimate Guide to Easy, Space-Saving, and High-Yield Terrace Gardening

- How to Grow Tons of Long Beans Easily Without a Garden – A Complete Guide to Growing Healthy Yardlong Beans Without Fertilizers or Pesticides

- Easy Long Bean Growing Trick – No Garden, No Fertilizer, No Pesticide

- Grow Bitter Melon in Bottles — Harvest So Big You Can’t Eat It All! The Ultimate Guide to Bottle Gardening for Maximum Yields

- Growing Garlic Made Easy: No Soil, Fast Results – The Ultimate Guide to Growing Fresh Garlic Indoors Without Traditional Soil

- Wall-Mounted Hydroponic Watermelon System: Grow Large, Juicy, and Delicious Watermelons at Home with Minimal Space and Maximum Yield

But the numbers, and what they mean, are starting to surprise even the people planting them.

A mangrove forest doesn’t shout its power. It creaks, drips, hums softly with insects and hidden fish. Walk between the roots and you feel the ground wobble like a sponge. The air is thick, salty, and a little sour. Birds perch above you, and the sun filters through a roof of tangled branches.

To many coastal communities, these messy trees used to look like wasted space. Something to clear for shrimp farms, resorts, roads. Then the storms got stronger, the seas crept higher, and people started to notice what disappeared with the trees.

Promoted Content

They hadn’t just lost trees. They’d lost a shield.

In the Philippines, for example, villagers in the province of Leyte remember Typhoon Haiyan all too vividly. Entire neighborhoods were flattened, and stretches of coastline stripped bare. Years later, a small community decided to replant mangroves along a battered bay. At first, it looked like a desperate gesture, a bit of green against a grey, rising ocean.

They planted anyway. A few thousand seedlings at the start. Then more, joined by school kids, fisherfolk, retired teachers. The saplings took root. Fish slowly came back. Shellfish clung to the roots. When a strong storm hit again, houses behind the new mangrove belt stayed standing while nearby bare shores flooded right through.

Stories like this, from the Philippines to Kenya to Colombia, add up. All together, they now amount to over 500,000 replanted mangrove trees across dozens of sites. Each one small enough to hold in your hand. Together, big enough to bend the future of those coasts.

Scientifically, mangroves are a carbon trap disguised as a tangle of roots. Their trick is simple: they store a huge amount of carbon not only in their branches and leaves, but deep down in their waterlogged soils. That mud below your feet may hold carbon that has sat there quietly for centuries.

Researchers estimate that hectare for hectare, mangroves can store up to four times more carbon than many tropical rainforests. That’s why you’ll see the term **“blue carbon”** everywhere in climate reports now. It’s the carbon held by oceans and coastal ecosystems, and mangroves are the star players.

When those forests are cut, that locked-up carbon leaks back into the atmosphere. Fire, drainage, bulldozers: all of them turn a carbon sink into a carbon bomb. Replanting 500,000 trees isn’t a magic spell, but it starts reversing that flow. Each seedling is like a small valve, slowly tightening the tap on emissions and opening the tap on storage again.

How Half A Million Mangroves Are Changing Coastlines

Replanting mangroves rarely starts in a lab. It starts with someone picking up a seed pod off the beach and thinking, “What if we put this back where it used to be?” In many projects, local fishers are the first to join. They know exactly where the water used to be calmer, where oysters once clung to the roots, where their grandparents’ nets came up full.

The method looks simple: collect propagules (the long, pencil-like mangrove seeds), carry them in buckets, stick them into the mud at the right depth, then hope the tides and crabs don’t undo your work. But behind that gesture lies a careful choice of species, spacing, and timing with the seasons.

The most effective projects work with how the water moves, not against it.

Take a project in Mombasa County, Kenya. Community groups began by planting a few hundred seedlings in a degraded creek. They studied how the currents flowed, where the silt settled, where waves hit hardest. Then they mapped out rows of seedlings in slightly staggered lines, like a living net across the water’s energy.

Within three years, the change became visible. Shoreline erosion slowed. Flooding during high tides dropped. Juvenile fish began crowding the submerged roots, turning the dark channels into nurseries again. Local women’s groups started small oyster and crab businesses, hanging baskets and cages in the shade of the young trees.

When they counted, they found thousands of new seedlings had sprouted naturally in the gaps between the planted ones. The forest had started to repair itself.

On paper, 500,000 mangrove trees sounds like a nice round figure in a report. On the ground, it looks like something else entirely. It looks like hours of muddy work, school uniforms stained brown, and meetings in community halls arguing over who uses which patch of shoreline.

Mangroves change the local economy as much as they change the landscape. Fishing patterns shift as new species return. Tourism operators suddenly realize that a boardwalk through shady trees is more interesting than another strip of white, eroding sand. Municipal officials begin to see that every meter of living shoreline is one less meter they need to protect with concrete.

Climate negotiators talk about gigatons and offset schemes. Here, the language is more basic: fewer floods, more fish, quieter nights when the storms roll in.

None of this means it’s easy.

What Works (And What Fails) When You Replant Mangroves

The most successful mangrove restoration projects tend to start with one humble step: asking people who live there what the coast used to look like. On a practical level, that means sitting with elders, bringing old photos, drawing rough maps in the sand. They point out where the channel once ran, where crabs were thick, where kids learned to swim under low, leafy branches.

From that memory work comes a simple but powerful method. Identify which mangrove species thrived where. Match seed to place. Plant at the right tidal height, not just where the land feels empty. Many projects now use small wooden sticks or shells to mark safe planting lines, so volunteers don’t guess.

They plant fewer trees, but in smarter places.

There’s a recurring confession from many NGOs and coastal groups: their first mangrove projects failed. Rows of trees died, washed out by waves or left high and dry. Soyons honnêtes : personne ne fait vraiment ça tous les jours. Most people learn by messing up, then trying again with less ego and more listening.

Common mistakes repeat from Asia to Africa to Latin America. Planting only one easy species, even where it doesn’t belong. Treating mangroves like a tree farm, in straight lines, ignoring the channels and pools that make a forest breathe. Ignoring local fishers who warn, “This spot floods too fast,” or, “The mud here is wrong.”

The projects that now boast thousands of surviving trees often carry a trace of those early failures. They moved to a slightly different bay. They changed the spacing. They worked out who would care for the seedlings between planting seasons.

There’s also a quiet emotional side that rarely makes it into glossy reports.

“At first it was just a job,” admits Rehema, a 32-year-old mother of three from coastal Kenya. “I got paid a small amount per day to plant the seedlings. Then one night we had strong waves. I came back the next morning and saw the water had stopped right where the new trees were. That was the first time I thought, ‘They protected my house.’ Now I bring my children here and tell them, these trees are your wall.”

That sense of ownership is what keeps a project alive after the funding cycle ends. When people feel the trees are “their wall”, they chase away loggers, replant gaps, and explain to newcomers why the muddy mess matters.

- Main lesson from the field: Mangrove recovery is less about planting as many trees as possible, and more about helping the right forest come back in the right place.

- *Best early sign of success:* crabs, snails, and small fish returning to the roots long before the trees look impressive from above.

- Most underrated factor: local stories and memories, which often map past ecosystems more clearly than any satellite image.

What Half A Million Trees Really Mean For The Rest Of Us

On a global scale, 500,000 mangrove trees won’t “solve” climate change. They won’t stop hurricanes, rewrite temperature charts, or let high-emitting countries off the hook. What they offer is more grounded, and maybe more useful for our tired, overexposed brains.

They show that climate action can be tangible, visible, and rooted in one specific shoreline. They show that protection and repair can happen in the same place, at the same time. A simple, slightly muddy practice that turns fear of the sea into a relationship with it.

That matters for anyone who has looked at the news and felt that quiet, heavy sense of “it’s all too big”.

On a personal level, mangrove restoration taps into something we rarely admit out loud. Many people want to help but don’t want another app, another pledge, another lecture about their guilt. They want to feel a change in their body: in their lungs, in their feet on the ground, in a shoreline that looks different when they come back a year later.

Even if you never touch a mangrove seedling, projects like these can shift how you think. Maybe you support a coastal group instead of buying another meaningless “green” product. Maybe your next holiday includes a visit to a mangrove walk, where you spend an afternoon learning how those roots hold more than just mud.

We’ve all had that moment where the climate headlines blur into one long, anxious scroll. The story of half a million mangrove trees isn’t a miracle cure. It’s a reminder that part of the answer is messy, local, slow, and strangely beautiful.

It smells like salt and rot. It sounds like wind in tough leaves. It looks like kids running between roots that will, if they’re lucky, outlive them by decades.

| Point clé | Détail | Intérêt pour le lecteur |

|---|---|---|

| Mangroves stockent un “blue carbon” massif | Elles emmagasinent jusqu’à quatre fois plus de carbone que certaines forêts tropicales, surtout dans leurs sols gorgés d’eau. | Comprendre pourquoi replanter ces arbres a un effet climatique disproportionné par rapport à leur taille. |

| Protection naturelle des côtes | Les racines ralentissent les vagues, réduisent l’érosion, et limitent les dégâts des tempêtes et des marées hautes. | Voir comment ces forêts peuvent protéger des maisons, des routes et des moyens de subsistance. |

| Reconstruction des économies locales | Le retour des poissons, crabes et coquillages stimule la pêche, le tourisme et de nouvelles activités génératrices de revenus. | Percevoir les mangroves comme un investissement vivant, pas comme un simple geste symbolique. |